What does it mean to enter a sacred space? When people enter Notre Dame, the light falls from the colored stained glass equally upon the devout and the non-religious. The same air surrounds, cooled by stone, and the same haunting music echoes quietly among the shadows.

Even the non-religious can feel its beauty and the spark of reverence it invokes. But is there a difference for one person over the other? Both are called here because of its sanctity, perhaps neither for religious reasons per se. But it is the sanctity of the cathedral that made it such an important site for devout Christians, and it is the sanctity that caused it to be built with such splendor.

But what of large roughhewn stones standing casually in a field? Do they too hold this sanctity? Religions throughout time and across the globe have segregated special places in which people can enter and associate with the divine. The ether touches our mundane world in these sacred spaces, which are as varied in form as there are beliefs.

From towering temples to natural grottos to nothing itself, in the ephemeral sacred emptiness – the religions the world over have pointed to this place or that and have said, “Here human, here is where the veil is lifted and the divine meets us.”

Traveling to a Sacred Space

With so much of history wrapped around religion and religious tourism being a popular travel niche, sacred sites all over have become havens for not only the spiritual, but also the curious. Sacred tours and sacred travel have been important both throughout history and in the modern age. Look on any city’s webpage for its history, archaeology, and architecture and you will see how tourism cannot help but come face to face with religion.

I am an independent historical researcher specializing in religion and mythology. My research is is featured in diverse publications, including the World History Encyclopedia and my YouTube channel. In this guest article, I extend an invitation to readers interested in traveling to sacred spaces and hope you find information and inspiration for your own visits.

But back to our original question, what does it mean to be in the presence of a holy site? How can we increase our understanding of what we are experiencing? To start, we begin by understanding what a sacred site is and then move on to contemplating the vast diversity of form and functions of these sites worldwide.

What Makes a Space Sacred?

It would be hard to have a discussion about sacred space without mentioning Rudolf Otto (1869-1937), the German philosopher and theologian, and Mircea Eliade (1907-1986), the Romanian historian of religion. They are both very influential in this topic.

Rudolf Otto traveled the world to explore ways in which religion manifested itself across the diversity of cultures. He came to call the Deity “the Wholly Other”. He sought to explain the meaning of holy and its contrast with the everyday world, the mundane.

Numinous Spaces

Otto created the term “numinous” which stems from the Latin word numen meaning “god”, “spirit”, or divine”. When a place feels numinous, the holy comes forth and that place is a separate space from the regular world. It is where people have had or can have a hierophany – a revelation of the divine reality. This is no small thing. Whether one believes in the literal event or not, the real-world consequences of such events are both apparent and common.

Axis Mundi

Mircea Eliade added to the conversation of what is a sacred space and what is ordinary. He coined the term axis mundi – meaning, the axis of the world. It is a place where the underworld, the earth, and heaven are connected through a sacred, central pillar – such as a tree, a pole, a mountain, an altar, or a temple. The cosmos turns around this axis.

A famous example of these pillars are Yggdrasil the cosmic tree of Norse mythology. Another is the Kaaba the most holy of Islamic temples, around which pilgrims circumambulate. An imago mundi is a representation of the rest of the cosmos around the axis, such as a city being built outward from the temple.

Sacred Emptiness

Another religious term to acknowledge is sacred emptiness. It is a deliberately empty space – void of anything mundane claiming to be a representation of God – in which the divine is given room to manifest. Here it is not the building, alter, statue, or natural feature that emanates the divine, but the lack thereof.

This idea also turns up more esoterically in certain mystic and religious practices where one empties their mind. This allows the Ultimate Reality to be revealed internally. Similarly, one can also explore the nature of God through apophatic theology. This is defining God through negation, what God is not: “God is not X. God is not Y.”

The most famous and dazzling example of sacred emptiness was in the Holy of Holies, the inner most chamber of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem. The God of Abraham would become the one God of the world’s three great monotheistic religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. And in His highly adorned temple of gold and copper, bull and cherubim iconography, and sacrificial smoke, his throne room laid nearly empty. Two magnificent cherubim with outstretched wings guarded the Holy of Holies, the meeting place of the Lord, who was symbolized as nothing. No image, no symbol, no statue. The God of Abraham was too great.

The Diversity of Sacred Sites Around the World

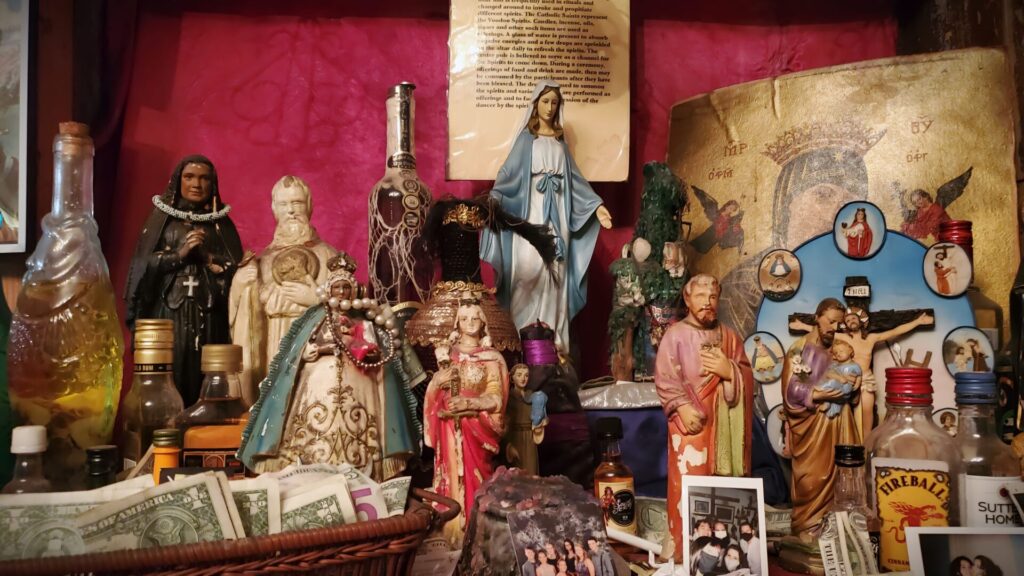

From the grandest structures ever created to simple private shrines in a home, cultures the world over have set aside spaces to be special, sacred, and where the Wholly Other can be experienced. Of course, no one can miss how churches fall into the category of sacred space, but the sacred isn’t always so obvious.

Let’s take a brief saunter around the world to see the diversity of sacred spaces where human spirituality has been expressed.

Hindu Temples and Shrines

There is no one Hindu religion; it is a complex network of varied traditions, practices, and mythologies. How a Hindu person practices their religion is often determined by their denomination and ethnicity, or their sampradaya. This a tradition focused on a specific deity.

Sometimes a mandir (temple) will be a sanatana (Sanskrit) or sanatan (Hindi) temple. This means it is ecumenical and appropriate for Hindu worship from any tradition. Hindu temples are famous for being large, grand structures with intricate ornamentation and carvings. Worship can also be done at small private shrines within the home. These shrines sometimes take up an entire room dedicated to worship, but can be also be on small shelves or in cupboards.

Whether at home or in a mandir, worship can consist of praying, singing, mantras, incense, food offerings, and caring for idols. All these types of sacred spaces in Hinduism are called devalaya, or “God’s abode”. Here devotees experience darshan – the beneficial act of being in the presence of a god and looking into each other’s eyes. For this reason, both temples and shrines include statues and/or pictures of deities.

These spaces must remain shuddh – “pure”. Hindus must be careful not to pollute their god’s space. For example, they perform ritual purification before worship. Also, a temple priest will not perform funerals. This is because funerals are considered contaminating and require a specialist to perform the function. It is important to understand and respect Hinduism’s emphasis on purity when visiting their holy places.

Ancient Standing Stones

Next, we turn to an extremely ancient form of sacred site – standing stones. Stonehenge is most likely the image that comes to most people’s minds when talking about standing stones. But did you know that they were used across the world in even much older times for religious and ritual purposes?

Standing stones from across the world are often monumental and were moved into place with a great deal of effort (although many are more petite). Standing stones are often aligned with astronomical events, such as the solstices or equinoxes.

Massebot

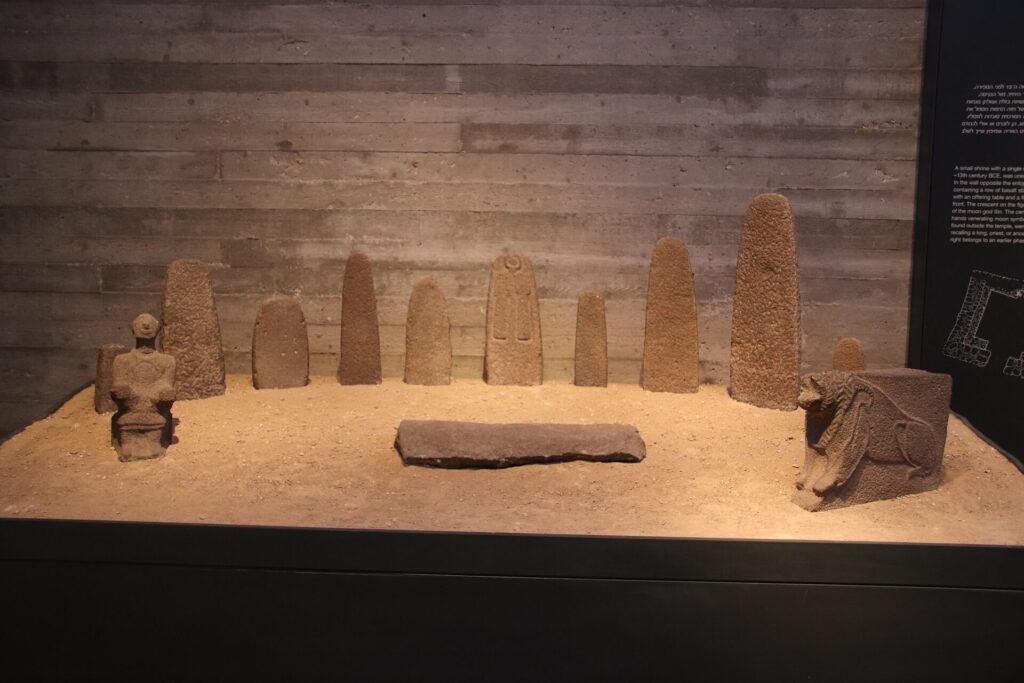

One example of these is the ancient Near East’s massebot. Massebot are standing stones of different shapes but are often semi-elliptical. None of them have anthropomorphic details.

They have been found in open air sanctuaries and in temples and temple courtyards all over the Levant, including Arad, Lachish, the Bull Site in Manasseh, Dan, Tirzah, and Hazor along with hundreds of sites throughout the Negeb and Sinai. Their use spanned millennia, starting in the Mesolithic Period and going through the 8th century CE.

Massebot stood as single stones or in groups, often of two, three, and seven. These are common numbers for deity groupings in the ancient Near East. They are an example of aniconism. They did not represent a physical likeness of a deity but still call upon the deity’s presence. You can read more about the ancient religion of Israel here.

The Labyrinth

The symbol of the labyrinth goes far back in antiquity, back to the Neolithic period.

However, the oldest known constructed labyrinth was in Hawara, Egypt. Flinders Petrie discovered the site of this labyrinth in 1886. Long before this discovery, it had been deconstructed, and it’s building material repurposed. However, in its day, this labyrinth was quite awe-inspiring to see. The Greek historian Strabo considered it comparably impressive to the pyramids.

Another famous labyrinth is the Minotaur’s on the island of Crete in Greece. This story is believed to have sparked from the complicated palace of Knossos built by the Minoans on the northern side of the island.

The Labyrinth as a Journey

But here and elsewhere throughout humanity, the labyrinth was not a temple for a god, but represented another aspect of human spirituality. It is not just a place but also a period of time, a journey. The labyrinth carves out a space where one embarks on a journey of self-knowledge, meditation, and life and death. One comes to the end changed, no longer the same person who entered.

This concept has pervaded human contemplation for many millennia. Mircea Eliade explained that labyrinths are archetypes associated with initiation rites and the cycle of nature. They are the gateway between life and death.

Carl Jung believed that the labyrinth was a symbol for personal growth and for the process of connecting the internal self and the outer. He states in his Stages of Life, “The meaning and purpose of a problem seem to lie not in its solution but in our working at it incessantly.” As one would go through a labyrinth, it is the journey not the destination.

Reasons for Labyrinths

Labyrinths have been used for many things, such as protection and magic. Fisherman in Nordic cultures used to walk stone labyrinths called Trojaborgs before setting out to sea. This was thought to increase their luck and to restrain bad spirits and trolls within their walls. Churches used carvings of mazes for protection.

They were apart of Native American, Northern European, Asian, and African cultures, among many others. Labyrinths are still being constructed today, as paths for self-discovery and meditation. This is because the concept of this winding journey has had such a visceral impact on the human psyche.

The Devil’s Tower

The Devil’s Tower in Wyoming is an example of how sacred space and modern entertainments can collide in an unfortunate way. While many churches and temples around the world have learned to blend tourism into their daily routines, sometimes benefiting from the revenue, the Devil’s Tower is a point of contention.

The 867-foot-high natural rock tower, formed from a volcanic intrusion, has became a United States National Monument. But for many Plains Native Americans, its significance reaches far back in time and is an enduring sacred site. The Arapahoe, Cheyenne, Crow, Kiowa, and Lakota all have similar stories with differing details about the creation of the tower, called Bear Lodge or Bear Tipi.

In each of these stories, the Great Spirit saved people from a bear attack by causing the rock to rise up and lift the people high into the air. The bears trying to reach those on top scratched the sides, causing the striation lines we see. The Lakota people call it Mato Tipila and still go to the natural wonder today to worship in this sacred space.

Managing a Sacred Space and Public Use

They have the misfortune of having to share this popular monument with climbers. The Bear Lodge is a great place for mountain climbers, but unfortunately the climbing peak season is in June which also happens to be an important religious month for the Lakota.

Lakota come to the tower to worship amid the athletes enjoying the spectacular views from this unique natural structure. Since 1996, the National Park Service has asked visitors to not climb the tower in June, although following this request is voluntary. While this does not let the Lakota worship in complete privacy, it has significantly reduced the number of climbers during their sacred month.

Should we favor the public’s enjoyment of one of the nation’s great natural wonders or defer to a relatively small population’s religion? Perhaps with just a bit more voluntary respect, we won’t have to choose.

Visiting a Sacred Space

The concept of spirituality and religion is uniquely human. While many animals value the lives of themselves and their companions, humans alone on this planet attempt to reach out beyond the physical realm and touch the sacred.

This practice goes far back into our past, back to our very early ancestors, at least over 30,000 years ago. Some speculate religion sprung from a desire to explain the seemingly unexplainable forces of nature. Some say that psychedelics may have played a part in sparking that first initial religious flame. Others believe it was our literal souls that were inspired to seek the truth, an innate and natural drive humanity has within. Whatever religion’s first cause, the history of the world has been animated by people’s ardent feeling of spirituality.

When we travel to places of spiritual significance, we become a part of their story – whether still visited by devoted practitioners or abandoned long ago as an artifact of time. Each of these places continue its journey through history as edifices of humanity’s distinctiveness and our call to the unknown and the unknowable.

What sacred spaces have you visited that have impacted you? Tell us about in the comments, we would love to hear.

This Guest Post was contributed by April Lynn Downey, M.A.

Follow April Lynn Downey on YouTube and at Phoenix and Feather Books and Curios Store – a fascinating online store and a portal to educational articles, historical consulting services, and a quarterly newsletter called Journal of Tales.